In the New Year, I've been trying to severely curtail my internet use. A side effect of this has been far fewer posts on this blog linking to articles or papers or videos that I've found interesting.

This is the next brick in a path I've been headed down for a while now. When I was a first-year med student, a classmate of mine was famously addicted to her flip phone. It would buzz and ring through lecture, and people would give her the stink eye, and as soon as the last Powerpoint slide clicked off the last reaction in the Krebs Cycle, she would bolt from the room and start making calls like a Wall Street veteran. Like Dan Akroyd in Trading Places. What would she have been like if she'd had a smartphone? Well, we know what she would've been like, because most of us are exactly where her trajectory was headed, and we're doing it with almost no social stigma. She would've answered all those calls with texts, right there in the lecture hall, and she would've checked multiple social media accounts to boot.

Needless to say, I was not an early adopter of social media. Once I had a couple accounts, I quickly found that social media made me act differently than I do in other situations or media. The act of trying to market myself for "likes" or "pins" on a platform of someone else's design was an act perfectly designed to produce insincere, awkward content. And thought I'm generally sincere, or at least I try to be, I'm somewhat socially awkward. That is, I'm awkward enough without someone else's help. I found that the effort I put into social interaction on platforms like Facebook and Twitter didn't enrich me. If anything, it impoverished me. It made me feel bad.

I was mystified by people's willingness to give up all the same information that we try so hard in the medical world to keep private. Facebook in particular seemed to be engineered specifically to tweak my smoldering social anxiety. It tried to choose my "friends" for me. But as I accumulated hundreds of "friends," the value of real friendship seemed to be degraded. And the privacy. Lordy. The day I put it to sleep came on my birthday a couple years ago. In spite of my almost religious tending to social media to keep details like the date of my birth off of them, people knew. Just like Wolfram Alpha knew. And I didn't want them to know. So I deleted it.

A year or so ago, I read Cal Newport's book Deep Work as part of a book club. I was still wading around the fever swamps of Twitter at the time, because I thought it was good to stay engaged for work. It wasn't completely by choice. I had suspended my Twitter account at one point, but then I'd applied for work with a company that used Twitter for much of its internal non-secure messaging. So during my grace period with Twitter (they give you a chance to come back for a month after you delete your account. Surprise!), I re-activated the account.

The discomfort with it remained. I started to talk about social media in less-than-flattering terms in posts a few months ago. Then I paused. I thought maybe I was being stereotypical: the middle-aged guy yelling at younger people to get off my digital lawn. But I kept some thoughts in draft form while I thought it over. I even considered getting a Facebook page for Double Arrow Metabolism, just to drive a little more traffic.

When the 2016 presidential election happened and I got glued to the daily outrage of social media as it responded to a shifting political landscape. I was left with two options: 1) master the software, or use it in such a narrow sense that it didn't control me, which seemed unlikely. I'm a reasonably smart guy, but my reptile brain can't outsmart thousands of computer engineers. Or 2) kill the software and get to know myself better. I don't mean blow up Twitter; I mean kill my interaction with it. I chose #2, eventually. I feared it would hurt business, or make me less knowledgeable about the world.

Then I read Newport's "any benefit" argument: we stay on social media because we can't bear the thought that there's some unknown, as of yet unseen benefit to it. In other words, what will we miss out on? It reminded me of what my parents lovingly called this the "unsmelled fart rule" when I was a kid. I'd be told to go outside, away from the party, and when I objected, I'd be asked, "What's the matter? You afraid somebody's gonna fart and you won't get to smell it?" That's exactly what I was afraid of with Twitter. But after I read Newport's book, I just quit. And it hasn't made a bit of difference in regards to my knowledge about the world. If something bad happens, I'm going to hear about it, social media or not.

So I've been off social media for a little over a year, I think. Scratch that-it's not completely true. I still have a Strava account, albeit with no notifications enabled. And I still have a LinkedIn page. LinkedIn is like social media status post fun-ectomy, though, so I don't really count it. I even experimented briefly with Figure 1, but I didn't think it was useful. If I'm going to look at cases, I want to either get money or CME credit in return. Figure 1 provided neither.

But it wasn't just awkwardness or privacy concerns that bothered me. It was a gnawing sense of unease. And I couldn't quite put my finger on what bothered me until I read Andrew Sullivan's piece about the phenomenon a year or so ago, "I used to be a human being."

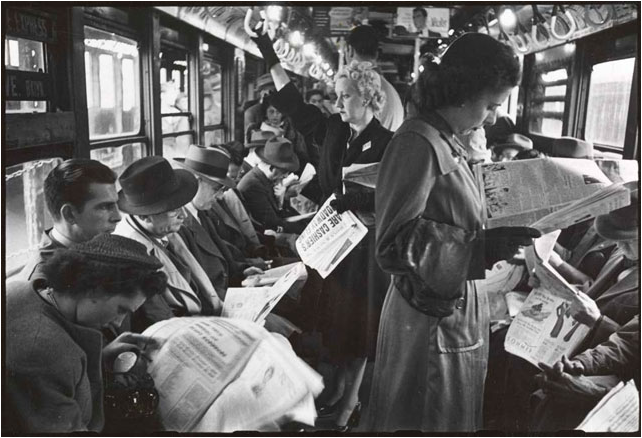

"Every minute I was engrossed in a virtual interaction I was not involved in a human encounter. Every second absorbed in some trivia was a second less for any form of reflection, or calm, or spirituality. 'Multitasking' was a mirage. This was a zero-sum question. I either lived as a voice online or I lived as a human being in the world that humans had lived in since the beginning of time.

And so I decided, after 15 years, to live in reality."

Time on social media, and now to some extent time on the internet, was taking away from time in the real world. You might be pointing out right now the apparent hypocrisy of the position I'm in the process of staking, since you're currently reading these words from a screen. Why, you're asking the screen (and by extension me), do you spew forth on this blog if you're so against public sharing? Fair point. But my content has decreased. And whether you like what I have to say or not, I don't make money off of it, even though I do make money off the consulting work that sometimes makes a guest appearance on the site. And I don't spend a lot of time looking at the analytics on my site to see how many of you are reading. So this particular shout into the void is my way of getting what I consider my fairly radical beliefs about health out into the world. But I figure the people reading this blog have at least a passing interest in me or in what I have to say. If you're here, I've in some way earned your eyes on this page. Artificial intelligence did not move Double Arrow Metabolism higher in your feed. So sure, I'll share with you, like the authors of some of my favorite blogs share with me:

Velominati, Kottke, Study Hacks, Wait But Why, Slate Star Codex, Mr. Money Mustache, Red Kite Prayer, Marginal Revolution

But I won't share with a thousand people who caught wind of my birthday through a complicated algorithm and are only posting about it because said algorithm makes it easy to do and makes them feel bad if they forget. I want to generate content that--good or bad--takes me longer to write than it takes you to view. Call it anti-Twitter.

So the fact that I'm not posting as many links is dual purpose: it keeps me off the internet, and it keeps me from turning this site into something I didn't set out for it to be. If what you want is a bunch of interesting links, many, many websites serve that purpose better than this one. One of them is Twitter. But Twitter has a fatal flaw in that it has no end.

Comedian Aziz Ansari, a guy who it turns out was a creep on a date, but who literally wrote a book on how technology has changed romance, has this to say:

"I’ll say, the times where I haven’t read that stuff, the stuff that I normally read on the Internet, just nonsense blogs or whatever, the next day I’ve felt like I’ve missed nothing...Cause you’re not reading it for the information. What you’re reading it for, and this is just my personal theories about this stuff, what you’re reading it for is a hit of this drug called the Internet...Like, here’s a test, OK. Take, like, your nightly or morning browse of the Internet, right? Your Facebook feed, Instagram feed, Twitter, whatever. OK if someone every morning was like, I’m gonna print this and give you a bound copy of all this stuff you read so you don’t have to use the Internet. You can just get a bound copy of it. Would you read that book? No! You’d be like, this book sucks."

Again, Ansari, a comedian whose job seems to have been created in a laboratory to achieve maximum benefit from social media, had this to say to Stephen Dubner of Freakonomics before adopting his new social media, internet-lite life philosophy:

"I never read anything. I’ve never read all these novels that are like these beautiful stories that have continued to have a resonance with people for so many generations, like beautiful works of art that I could read at any point. But instead, I choose not to read them. And I just read the Internet. Constantly. And hear about who said a racial slur or look at a photo of what Ludacris did last weekend. You know, just useless stuff. It’s like, I read the Internet so much I feel like I’m on page a million of the worst book ever. And I just won’t stop reading it. For some reason it’s so addictive."

Aziz quit the Book of Internet. The Book of Internet is a shitty book. Double Arrow Metabolism will not be a chapter.

Since my departure from social media and my sharp reduction in internet consumption in general, I haven't come across much to change my mind. I read Jean Twenge's Have Smartphones Destroyed a Generation? I read John Lanchester's A Criticism of Facebook. They reminded me of a teaching course I attended at Beth Israel in Boston in roughly 2009, when "teaching the 'millenial learner'" was already a hot topic. They were different than Gen Xers and Gen Yers, we were told, in that they hadn't been quite so "latchkeyed" (a term d'art for what some might consider excessive babysitting as a symptom of absent parents). They also were perceived to want more of a personal touch in their instruction; more feedback. But Twenge notes that in her data, something shifted a few years after my teaching course on millenials. It was in 2012, the year that smartphone ownership in America surpassed fifty percent. So she calls the group at the tail-end of millenials the "iGen." Smartphones and social media have been ever-present in their lives. They've never known a world without tablet devices. Three out of four of them own an iPhone.

Rusty's Last Chance, a landmark bar in the Aggieville district of Manhattan, Kansas, was a beacon to Kansas State University students and nearby Fort Riley soldiers for decades, but it closed in February of 2017. Bars and restaurants close all the time, but I cannot help but think, based on my experiences in going back to Manhattan in recent years, that students' taste for virtual contact over the real thing didn't have something to do with it. I'm still volunteer faculty at the local med school, and one of the criteria we're expected to evaluate students--med students! Adults!--is their willingness/ability to stay off their phones during sessions.

At this point, if you're still reading, maybe you're ok with all this. Maybe you don't think your time is worth that much, and maybe you've heard if you aren't that bothered by an algorithm guiding you away from your true self, and maybe then that information you've paid to give up is used to reduce you to a set of numbers or yes/no questions that define you, just as medicine so imperfectly tries to define you by race, body mass index, blood pressure, and soon your genetic "fingerprint." After all, teen pregnancy is at an all-time low, and teens' addiction to their phones surely has something to do with that. It's hard to impregnate someone if you're spending your weekends in your bedroom scrolling through Snapchat. And kids are physically safer than ever; it's hard to die in a drunk-driving accident from the comfort of your bedroom, and I've never seen a drinking game whose rules involved immersion in tindr (but, come to think of it, I'm sure it exists). Psychologically, though, kids may in trouble. Twenge notes that since 2011, depression and suicide have "skyrocketed." I'm not sure this is true. I'm too exhausted by the internet right now to go and find the primary data. But it doesn't take a social scientist to watch toddlers engrossed in YouTube Kids at the grocery store and deduce that we're in the middle of a profound change. We're running an uncontrolled experiment on ourselves and our kids.

So how should we handle smartphones with our kids? Based on no empirical evidence whatsoever, my wife and I have decided that 1) our kids will not have their images posted on social media other than in extremely rare circumstances (nobody wants to be the guy that torpedos an entire birthday party, after all). And our kids, upon entry into middle school, will have access to a good, old-fashioned cell phone. But if they want a smartphone, they'll have to earn the money for it themselves.

At home, we try to enforce what I'll call the "White House" rules. I don't know how the White House handles the issue precisely, but I'm fairly certain that unsecured cell phones are a no-no in the White House. So, like a Jack White or Chris Rock or Dave Chappelle show, people are asked to put their phones away upon entering. So I follow the same rules: when family members come into my house, they put their phones in a central location, and we go about our business.

In case this all just sounds like so much "get off my lawn"-style old man grouchiness, I engage with technology. I help docs run their electronic medical records more effectively and efficiently. I listen to podcasts in my free time. But I can listen to podcasts while I accomplish other things. And EMRs, at least in theory, have value beyond the immediate.

Sigh. So that's the story. Expect fewer posts on this site than there used to be, because I'll simply have less to post, because I'll have spent less time on the internet than I once did. But I'll probably keep my smartphone. I like the calendar.