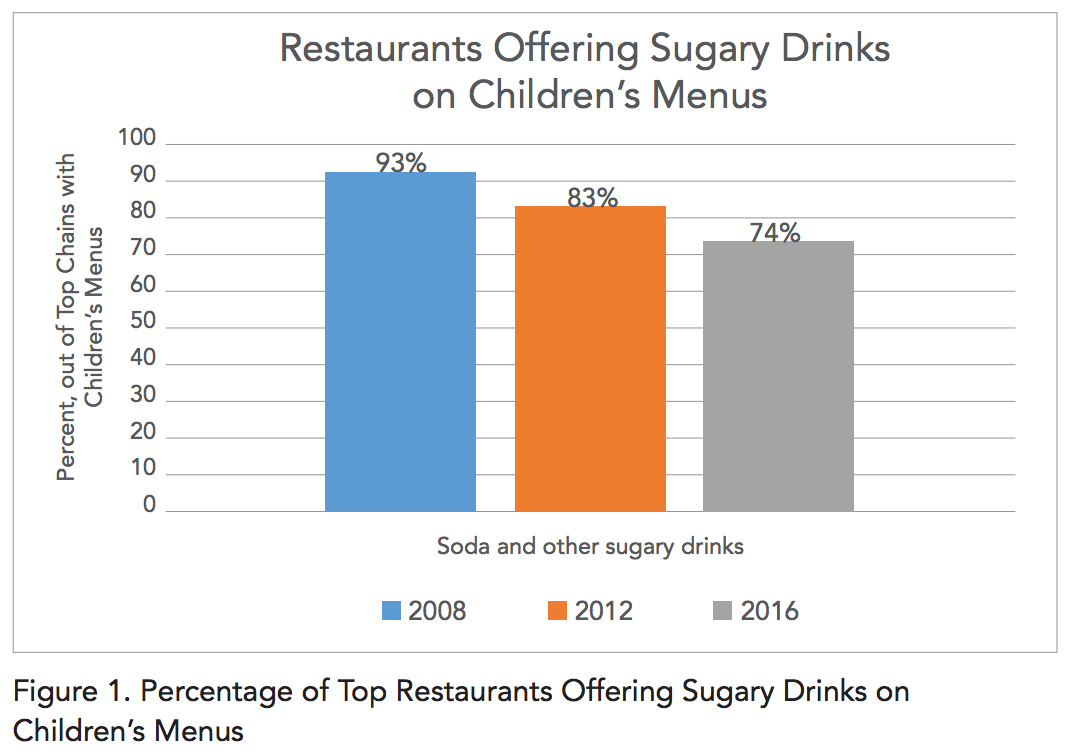

The rate of new COVID-19 cases is finally headed downward again in Kansas:

Statnews.com

We’re not through this yet.

With fall comes cooler weather and seasonal influenza stacked on top of the COVID-19 pandemic. This looming threat is causing foundational changes in our expectations of the season. Several college conferences have already cancelled sports. Theater releases of movies that cost hundreds of millions of dollars to produce have been delayed indefinitely, and others have gone straight to video on demand. The spookiness of the Halloween season is real, and getting realer every day.

So we and our employees should continue masking. Masking works (as long as the mask isn’t a fleece buff). We should continue socially distancing whenever possible, and we should obviously get vaccinated against seasonal influenza when we can. We should get the COVID-19 vaccine as soon as it is available. But what else can we do?

We can lose weight. Real disaster preparedness isn’t hoarding water or ammunition. It is largely the preparation of your body and your bank account for emergencies. A recent study in the Annals of Internal Medicine found that, especially in people younger than 65, obesity was one of the biggest risk factors for intubation and death with COVID-19. And the bigger patients were, the higher the risk. “Morbidly” obese COVID-19 patients–those with a body mass index, or BMI, of 40 kg/m2 or greater–were 60% more likely to die or require intubation, compared with people of normal weight:

Annals of Internal Medicine

And obesity may even decrease the effectiveness of a future SARS-CoV-2 vaccine.

So if you are one of the roughly 40% of Americans who are obese, then to protect yourself this fall, the time to start reducing risk is now. This isn’t about judgement or shaming. I’ve been very vocal in the past about my disdain for the opinion that obesity is some personal or moral failing. It is not. It is a product of genetics and environment, just like heart disease, cancer risk, and yes, risk for infections.

How can you, as an employer, help your employees reduce risk beyond vaccination?

Traditional worksite wellness programs are disappointing, unfortunately, although as we’ve blogged about in the past, some worksite strategies for weight loss have proven modestly effective around the holidays. And restricting one’s diet to “unprocessed” foods such as those in Group 1 of the NOVA Food Classification System appears to result in weight loss even without intentional dieting. If we take the problem seriously, though, we’re inevitably led to the question of coverage of weight loss programs like the Diabetes Prevention Program, coverage of weight loss medications, and coverage of bariatric surgery. [Disclaimer: KBGH is funded in part by two CDC grants that aim to identify obese or pre-diabetic people and refer them into programs like the Diabetes Prevention Program that help them lose weight and reduce their risk.]

If you’re not already covering these benefits, consider them the next time you update your employee benefits. And, as always, if KBGH can be any help in determining the potential benefits to your employees from these programs or treatments, please contact us!

As the Medical Director of the Kansas Business Group on Health I’m sometimes asked to weigh in on topics that might affect employers or employees. This was a reprint of a blog post from KBGH.