There are these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says, "Morning, boys. How's the water?" And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes, "What the hell is water?"

-David Foster Wallace

I don't know exactly what the late, great DFW meant by this. Tragically, he's not around to tell us. But what I think he meant is that the most important realities are often the ones that are the hardest to detect. And to continue to borrow DFW's analogy, most of us paddle forward as best we can without ever feeling the flow of water against us, pushing us back, keeping us from reaching our potential. That rush of water consists of a lot of things, but most of them are visible if you look closely.

I’m a physician, as you might have deduced by the initials after my name. And physicians by training are supposed to notice the things that others don't. But most of us don't, and I've been more guilty of this than anyone in the past. See, I'm an endocrinologist. That’s a specialist in metabolic and hormonal disorders (think disorders of the pituitary, thyroid, and adrenal glands; and osteoporosis and diabetes and whatnot). You’d think that an endocrinologist is a person particularly well-trained to help patients escape the vortex of fancy motorized wheelchairs, faux-food, time-sucking devices, and all the other things pulling us under.

But that’s not at all what I was trained to do. In fact, I found during my career as an academic endocrinologist that instead of getting people safely to shore, I was often quickening or deepening the vortex that my patients were swimming in. In 15-minute office visits, I’d prescribe drugs that cost thousands of dollars and have trite, brief (in case the 15-minute visit didn’t give it away) conversations about what they could do with their weight, or their fatigue, or their sadness. The visits cost me 15 minutes, that is. They cost my patients a lot more. A lot more.

I was doing my best, obsessing over the things I could measure or manipulate, like blood sugars, cholesterol, blood pressure, and weight. All those are important. Don’t let anything you read here convince you otherwise. But I was swimming in the vortex myself. I simply paddled forward in the water I was trained to swim in, comfortably moving myself from today into tomorrow, spending the loads of money I made on things that didn’t make me happy and working extra hours to pay them off. I drove like a maniac between two clinics and four hospitals, often putting almost 100 miles a day on my car. The vortex deepened. The extra hours ate into time that I should have spent doing things I loved, like chasing my kids or riding my bike, so I weighed thirty pounds more than I wanted to. The water sped up. And then my blood sugars--one of those things I prided myself on controlling--started going up. And then I started getting really unhappy and resentful at work. I was swimming as hard as I could, but spiraling. What I couldn’t detect was that I and my patients needed to become people again.

What’s that? My patients weren’t people? What am I, a veterinarian?

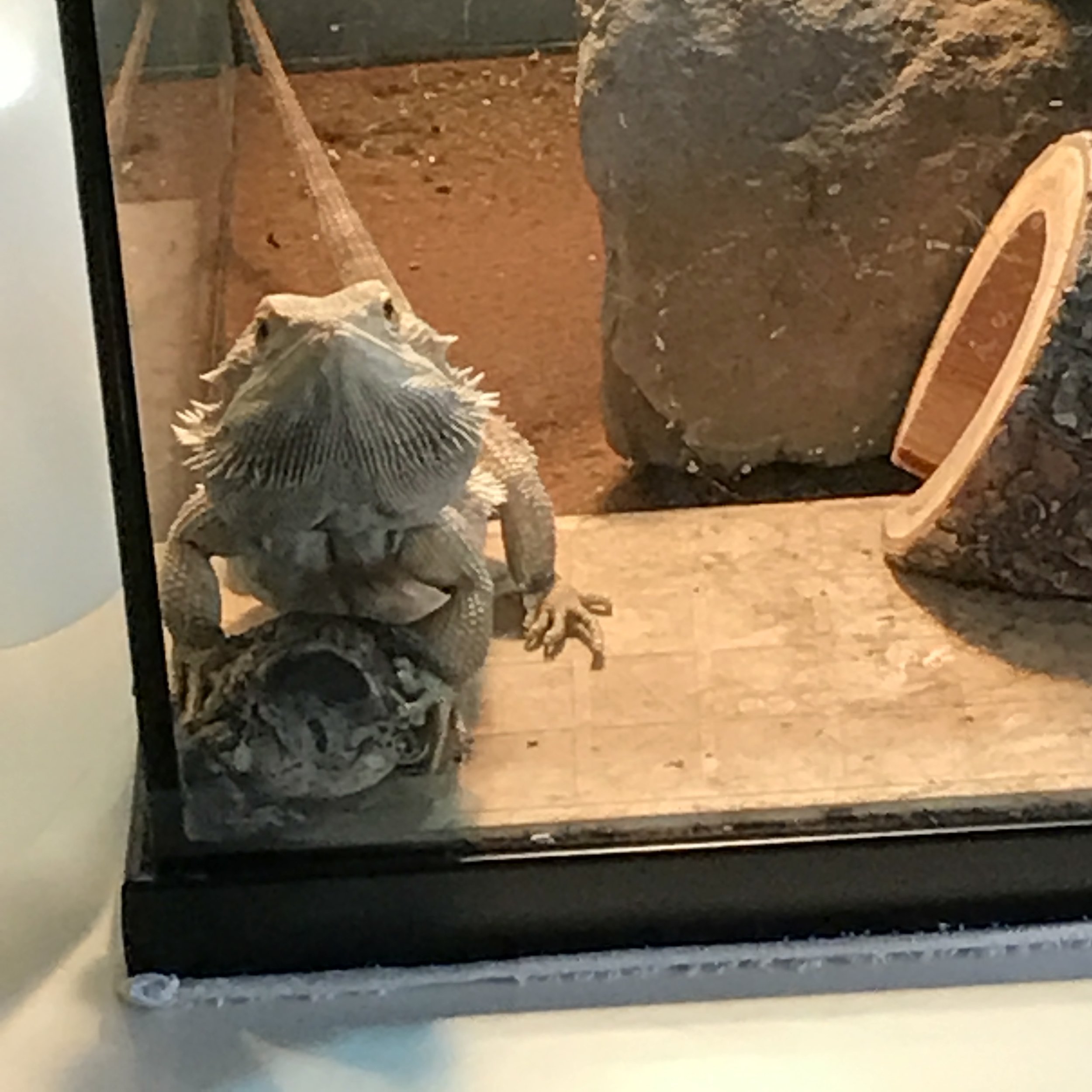

P. henrylawsoni can out-wrestle A. woodhousii any day of the week.

What I mean is, that once a person crosses that gauzy threshold from the waiting room to the exam room, he experiences a transition from personhood to patienthood. And patients are bad swimmers. Let me illustrate. Most of us, whether we’ve thought about it or not, exist somewhere on this spectrum:

I feel great. I’m as healthy as I can be, and I’m intentionally doing things daily to improve my health.

I’m healthy, but mostly by accident.

I’m not sick, but I don’t feel good. I’m always stressed out.

I have one or two health problems that I manage pretty well, but I’m broke.

I have a few health problems that I struggle to manage, I’m broke, and I’m working a second job to pay medical expenses.

I have been hospitalized one or more times in the last year for chronic health problems, and I can’t work.

I’m in a nursing home or assisted living because I can’t take care of myself anymore.

I am dying.

The thing about this spectrum is that the strategy for moving up on it depends on where you start, and it’s never a straight line. If you’re one of the unfortunates at #7 or #8 that our system most definitely calls patients, my thoughts are with you. If you are at #5 or #6, your strategy for moving up may involve a lot of pharmaceutical help. I have opinions, at least metabolically speaking, on what that help might look like. But if you’re at #4 or above, and you’re working on getting to #1, the path to get there may meander through the local pharmacy for a bit, but most of the path is outside in the sunshine and fresh air. The path most definitely does not intersect with your couch.

So by reading this blog, if you’ll bear with me, you’re going to learn to feel the water around you, and you're going to get the skills to map out your own path out of the evil vortex. I intend to be completely honest and transparent about what I know and what I’m not so sure about. There’ll be philosophical stuff, like what a good partner in health ought to offer. There may even be diversions into seemingly unrelated topics, like pop culture, the weather, or my favorite, cycling. If I haven’t scared you off yet, come back for the next post.