I spoke today at the Intersections of Faith and Healing Conference in Salina, Kansas. Here are my slides.

Monday, July 31 link-o-rama: good neighboring, CTE, mysterious illnesses, and drug-smuggling Mexican ultramarathoners

Is good neighboring good medicine?

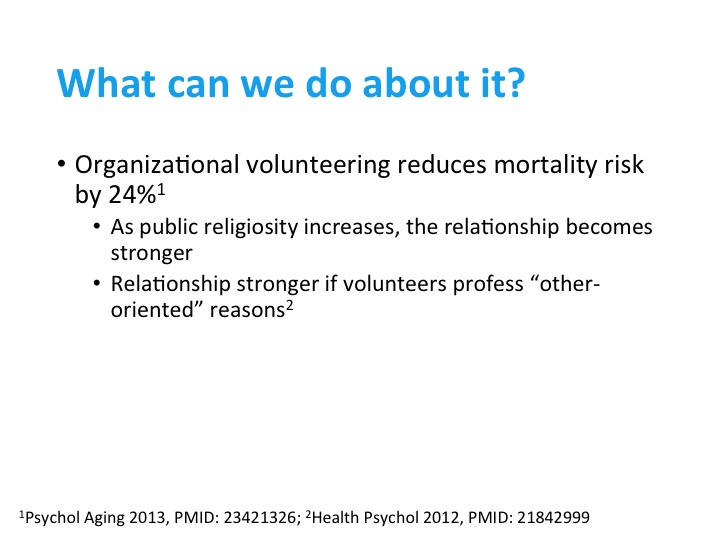

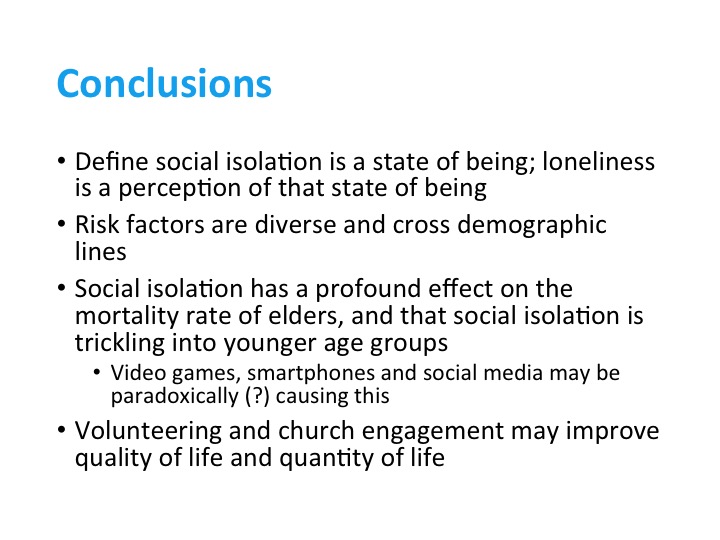

A few weeks ago, I was asked to give a plenary at the Chronic Disease Alliance of Kansas, in part on emerging threats. One of the emerging threats I highlighted was social isolation, which increases your risk of death by about a quarter. The reason I brought it up wasn't the shocking statistic (we've known that for a while, and we know people spend more time alone as they age), but because we're now seeing a remarkable rise in the number of young men not working and filling their excess time with video games (covered in a previous link dump; near the bottom). I've become interested enough in the topic that I'm hosting a workshop on it at October's Intersections of Faith and Health conference in Salina. So I was thrilled to see James Chung's well-produced (as always) video looking at ways for local people to be better neighbors. If the data is to be believed, it could be a really powerful intervention.

John Urschel, NFL offensive lineman and erstwhile MIT math grad student, abruptly retired after the JAMA publication of chronic traumatic encephalopaty data (covered in a previous link to health).

He has something to fall back on other than football. Bold prediction: this is the start of a trend. Football will gradually become like boxing and attract mostly down-on-their luck types who don't have another option for income. Or the NFL will make wholesale changes to the way the game is played (just kidding; that'd never happen).

Living with a "none of the above" disease.

This article on poorly differentiated syndromes and the promise of genetics in solving them is (rightly) pretty hard on doctors. But I'm curious about what patients and families would like out of doctors who are presented with unsolvable conditions (unsolvable with local expertise, maybe, but maybe unsolvable altogether). When I was still in full-time academic practice, I saw 2-3 patients per day with chronic fatigue as their presenting symptom. I do not recall ever coming up with a unifying diagnosis for any of them, although we certainly found some previously unknown diagnoses. I would have been happy--thrilled, actually--to send them somewhere that had resources and expertise to look more closely at their disease states. But I just didn't know or didn't have the resources. And I know most of those patients left thinking I was a bad doctor.

The Tarahumara of northern Mexico, made famous by the book Born to Run by Christopher McDougall, are being coerced into smuggling drugs by cartels.

Or temple, or mosque, or pagoda, or coven, or whatever. That's cool.

Go to church, you heathens, and adopt a perspective of abundance

I can remember one time in my life that I've asked God for help. I'm not proud of that fact. There were surely other times that I can't remember right now. I think my privileged life has something to do with it; I just haven't had that many chances to suffer.

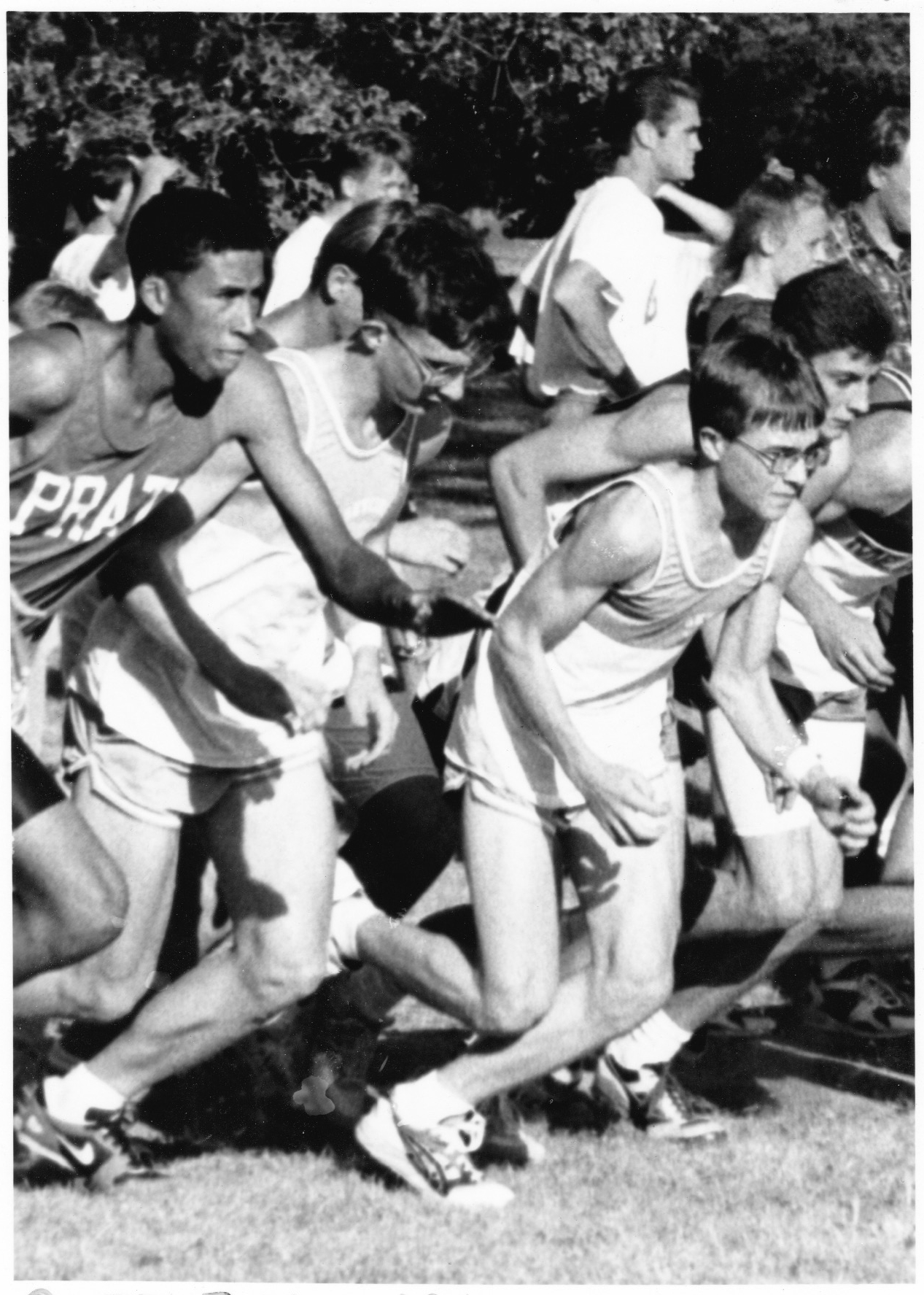

It was in my senior year of cross country. I was running my hometown meet.

Bowl cuts forever.

High school cross country races are a relatively anonymous affair. They don't draw big crowds, because people don't want to drive two hours to watch a twenty-minute race. So being at home was a big deal. I wanted to give the home crowd what it wanted, I guess, so I foolishly tried to keep pace with a kid from Liberal who was much, much faster than me. The race was 5k (3.1 miles), and at about 2.5k I knew I was in trouble. I figured I could limp home and still finish in the top ten (and I think I did, but I can't prove it). But to do so would mean going to a very dark place. I made promises to God that day, and I ran one of my fastest times: 16:59; not world-class, I know, but fast for me. If God had anything to do with it, I haven't remotely repaid the favor.

But I digress. This post isn't about my religion, or lack thereof. I attend church, but I'm not what any religious person would call a believer. Some of it boils down to the fact that I'm a bit of a skeptic in general and even more of a hermit. I'm simply more comfortable being alone than being in crowds. But being alone isn't good for me. So off to church I go most Sundays, wife and kids leading the way. And I frequently get something out of it, in spite of my smoldering skepticism. Take a couple Sundays ago, toward the start of Lent: our pastor brought up Nicodemus, the Pharisee who visits Jesus one night and serves up a big steaming pile of skepticism:

Nicodemus, in John 3:1-3:15, gets to play Scottie Pippen to Jesus's Michael Jordan.

Later on he reminds the rest of the Sanhedrin that the law mandates that a person be heard before he's judged, and later he helps embalm Jesus's body. And even later on, a group of newly-freed slaves founded a badass frontier town in his name in northwest Kansas. (which they only managed to hang onto with the help of some Osage, but that's another story)

Nicodemus deserves some credit here for asking Jesus questions about his radical philosophy. And the answer Jesus gives boils down to this: See your world through the lens of abundance, not scarcity. I think this philosophy applies to all of us. We're genetically programmed to cram high-fat, high-salt, high-sugar food into our mouths and lie on the couch because we evolved in an environment where calories were hard to come by, and where it took a helluvalotta work to extract them. But we also developed brains capable of rational thought, and now here we sit in an environment of caloric abundance, not scarcity. What we're programmed to seek now destroys us. It's as if we need water to survive, but we're being pulled into the center of a sucking whirlpool, being submerged in water that in excess quantity has become toxic. We're drowning.

Through a lens of scarcity, we are compelled to hoard calories and stuff them in our bodies as quickly as we can. And we're similarly compelled to preserve those calories by kicking back in a La-Z-Boy. But our evolved brains tell us that we don't need to do this. Through a lens of abundance, the path toward happiness doesn't pass through a cheeseburger.

Roadblock.

Instead, the path gently curves around that cheeseburger through something more sensible. Ultimately, you're happier if you skip the cheeseburger and eat something you won't regret later. This isn't a matter of deprivation. This is a matter of titrating our cheeseburger intake, just like we adjust our amount of driving or spending or physical activity, to achieve the maximum amount of happiness.

From a perspective of scarcity, your neighbor's new car induces a twinge of jealousy. But from a perspective of abundance, you can see the year's salary you saved by driving your perfectly good ten year-old car as a reward for the regular 30-minute walks or 10-minute bike rides to the grocery store. A perspective of abundance sees these walks not as a chore, but as a choice. Or better, an opportunity. And if that opportunity coincides with, as writer Florence Williams calls it, a reversal in your "slow telomeric death march" (I'm paraphrasing), all the better.

So back to church. Economist Jonathan Gruber from MIT has written about the effect of religion on well-being, and his thoughts were recollected in J.D. Vance's Hillbilly Elegy. Not only are people who go to church healthier and happier, but the effect seems to be causative. That is, church attendance seems to have caused people to be healthier and happier, not just that healthier and happier people tend to go to church more. To a skeptic, or to an *ahem*, coastal elite, there is a reasonable assumption that this personal benefit comes at a societal cost, since people who go to church are less tolerant than people who don't. And when it comes to some specifics like gay marriage, that's true. But for many other things, like immigration, religious people are much more likely to be tolerant if they're a regular church goer than if they identify as religious but stay home on Sundays.

As Easter dawns, I'm sitting in western Kansas wondering what it is about the morning ritual of church that makes people healthier. My religious half says that recognition of a higher power comes with benefits: I scratch God's back, he scratches mine. But my scientific half says that it's not the religion that's doing the trick. It's probably the community that matters. The act of putting the needs of a group of people before your own surely causes some reapportionment of the mixture of good and evil humors that make up our sense of well-being. So if church or temple or mosque isn't your thing, join the PTA. Or volunteer at a soup kitchen a couple times a month. Or help with your community's health assessment. Do pedestrian/bike counts on the public paths when they're looking for volunteers. Volunteer at Boy Scout camp. Whatever your church becomes, do the duties it requires from a perspective of abundance.

You might live longer. You might be happier.

Happy Easter!