As the Medical Director of the Kansas Business Group on Health I’m sometimes asked to weigh in on hot topics that might affect employers or employees. This is a reprint of a blog post from KBGH:

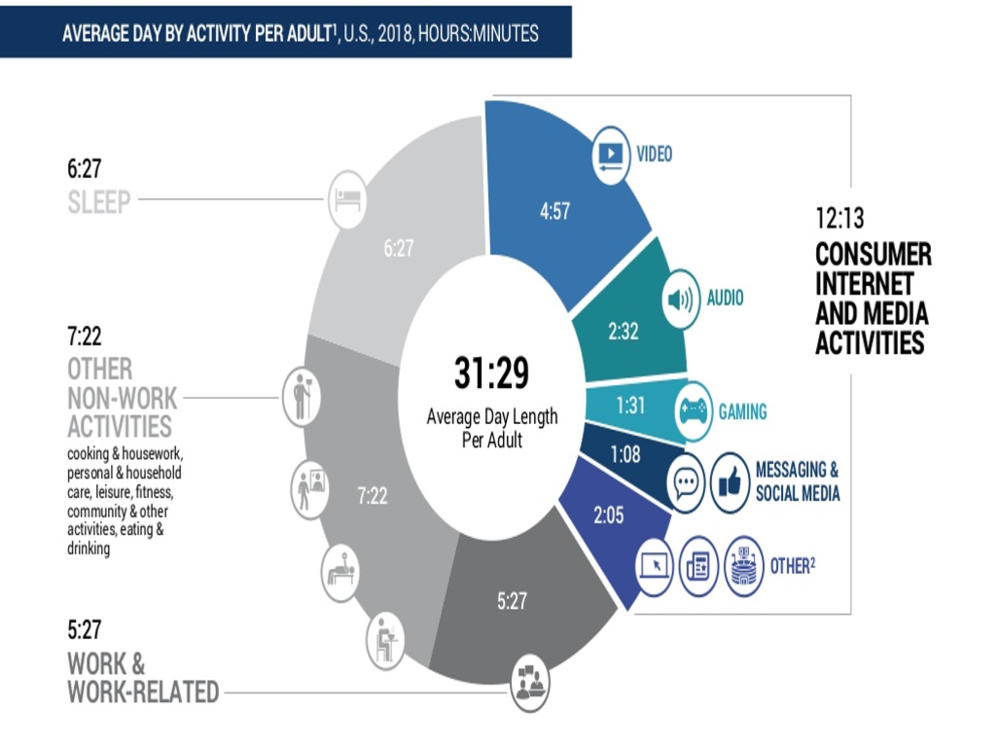

Social media takes up an inordinate amount of our time. A recent report by Activate Consulting found that, when multitasking with consumer internet and media activities are accounted for, the new “normal” day is 31.5 hours:

The amount of time we spend on these platforms is not likely to go down. According to that same Activate Consulting report, the number of social media networks an average person participates in is projected to almost double in the next four years, from 5.8 to 10.2 per user.

And in spite of snarky comments—many of them, yes, on social media—about the habits of millennials or Generation Z, it is Gen X workers in their forties and fifties who are the heaviest social media users, at almost seven hours per week, rising about 17 minutes per year.

All this virtual communication may be bad for us. Studies that are now several years old show that the more Facebook you use, the worse you are likely to feel. As anyone who has ever been accidentally pulled into an email argument that could have been solved with a single two-minute face-to-face conversation can tell you, in email and on social media in particular, we may abandon social norms in response to feedback from other users, since the algorithms that drive the platforms reward content that is highly emotionally charged. Tweets that use the greatest amount of moral-emotional language are the most likely to be retweeted or liked. Facebook posts that display not only disagreement, but indignant disagreement, are more likely to be liked or shared.

Why is this?

Researchers believe that virtual conversations lack the “advanced analogue cues” that in-person, video, or phone conversations have. Without clues like body language, tone of voice, and facial expressions, we have a hard time discerning the true intent or meaning behind innocuous statements.

What can be done?

A randomized trial by Stanford investigators showed that people who were paid to deactivate their Facebook accounts—as compared to people paid to continue their usual activity—were happier and reported increased well-being, decreased political polarization, and increased time spent with friends and family. And, presumably because of the drug-like effect of social media platforms, people who were paid to discontinue Facebook experienced apprehension at re-starting, just as a former smoker may be nervous about going outside around other smokers at break time.

But because of the strong network effect of social media, asking employees to cancel their accounts is probably unrealistic. Instead, we should look for healthier ways to use the platforms. After sifting through the mainstream medical literature, here are some of our tips:

Encourage your employees to use social media as a bridge to in-person connection and real experiences, preferably outdoors and definitely away from screens. Using social media this way to connect to other people you’ve lost touch with may even have profound professional benefits.

Create this bridge to in-person connection by changing the way you approach social media. Do not seek “likes.” Do not like other people’s posts, even though that may seem rude at first. Instead of passively scrolling through your Twitter, Instagram, or Facebook feed and hitting the “like” button, intentionally reach out to people. One study found that even one week of increased composed, directed social media posts to friends and family increased happiness. Another study compared this strategy to simply “liking” or sharing posts on Facebook. People who received targeted, composed messages from friends or family felt better; those who simply got “likes,” status updates, or shared posts experienced no change.

Encourage employees to enforce “sacred spaces” where no devices are used, in order to reclaim conversation and non-verbal advanced analog cues. At home this may mean the kitchen, the dining room, and the bedroom, since even the presence of a device on the table may alter conversations, and looking at bright screens before bed can disrupt sleep (to say nothing of sex). As technology researcher Sherri Turkle famously said, “The greatest favor you can do to your sister, mother, lover, professor, student, is put away your phone.”

While you’re at it, encourage employees to delete all social media apps from their phones and use social media only on a device they have to seek out, like a desktop computer. If that seems too severe a step, encourage them to go to their phone’s settings and kill notifications from all social media.

Are there strategies you’ve tried, either at home or in the workplace? We’d love to hear them!