With the pending transition in Presidential administrations and a historic pandemic killing more than 1,300 Americans daily, we are in for a lot of health care policy talk over the next few months. To refresh our fund of knowledge about American health care, we at KBGH have decided to outline the big features over a series of posts. Much of this comes from Ezekiel Emanuel’s excellent Which Country Has the World’s Best Health Care?

Contrary to popular media, there is no “American Health Care System.” Instead, we have a patchwork of independent and overlapping systems, each with its own problems, bright spots, and idiosyncrasies. This week we’ll cover public insurance.

What do we spend on health care?

The United States spends more than $3.5 trillion annually on health care, equivalent to about 18% of gross domestic product, accounting for almost $11,000 per person. This is roughly double the per-capita average of Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) peer countries like Japan and western Europe.

Where does money come from?

Roughly 45% of American health care is publicly financed: 28% federally and 17% by state and local governments. Medicare costs almost $600 billion per year, or 2.9% of gross domestic product (GDP), and covers 55 million senior and disabled Americans. Medicare Part A, covering hospitalizations, is funded by a 1.45% payroll tax from employers along with a 1.45% payroll tax from employees (plus another 0.9% payroll tax for individuals earning >$125,000 or couples earning >$200,000 annually).

Optional Medicare part B, covering physician visits, is financed by income-linked premiums averaging ~$130 per month for people who elect for the coverage. The premium covers ~25% of the cost, and the federal government covers the remaining 75%.

Medicare part C, or “Medicare Advantage,” can charge enrollees additional premiums.

Medicare part D is paid for by premiums paid by elderly beneficiaries and by other general governmental tax revenue.

Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) collectively cover 65 million mostly poor patients along with certain blind and disabled persons. Some beneficiaries are “dual-eligible,” meaning they are also covered by Medicare. The federal government pays ~57% of the cost of traditional Medicaid as the “Federal Medicaid Assistance Percentage,” while states cover the other ~43%. Medicaid accounts for 1.9% of GDP, or roughly $400 billion per year from the federal government. In many states Medicaid is the single largest fraction of the state budget. In expanded Medicaid under the ACA, in which Kansas does not participate, 90% of the cost is borne by the federal government with 10% borne by the state to cover patients whose income falls up to 138% the federal poverty line.

Kansas uses a “managed” form of Medicaid in which Medicaid is facilitated through third-party payers (Sunflower Health Plan, UnitedHealthcare Community Plan of Kansas, and Aetna Better Health of Kansas).

In Kansas MediKan covers adults with disabilities who do not qualify for Medicaid but whose applications for federal disability are being reviewed by the Social Security Administration. MediKan covers a scope of services similar to that covered by Medicaid, but with additional restrictions and limitations.

CHIP provides health insurance for children whose parents make too much to qualify for Medicaid but whose private health insurance does not allow them to get their children insured. CHIP is not open-ended like Medicaid, but is rather a block grant system varying slightly by state. The federal government pays 72% of the cost up to a year’s maximum allotment, and the State provides the remaining 28%.

The Veterans Health Administration (VA) covers 9 million former military service members. 2.2 million people of Native American descent are insured through the Indian Health Service (IHS). 9.4 million active-duty military and their families are covered through Tricare.

Where does the money go?

About 85% of health care spending is for chronic conditions like diabetes, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and high cholesterol. About a third of patients with a chronic medical illness also have a comorbid psychiatric disease like depression or anxiety. This is thought to increase the cost of care of those patients by 60% or more.

Hospitals consume about $1.1 trillion, or 33%, of all health care spending

Medicare Part A covers hospitalizations. Hospitalizations are covered according to “Diagnosis-Related Groups” (DRGs), fixed, pre-specified amounts paid according to the diagnosis codes attached to the hospitalization. Medicare’s DRG rates are set by the federal government. Medicare does not negotiate DRG payments; hospitals may take them or leave them. But Medicare does adjust the base DRG rate via special payments to rural and other hospitals, via “Disproportionate Share Hospital” payments to hospitals who provide a large volume of uncompensated care, and via two forms of additional payment to hospitals who provide graduate medical education to resident physicians.

Hospitalizations in Medicaid are covered according to DRGs, with prices set by the states.

The VA owns its own hospitals.

Physician payments consume about $700 billion, or 20%, of all health care spending

American physicians are well-paid: primary care doctors like family physicians, pediatricians, and internists make an average of $223,000 annually, and specialists make an average of $329,000, though that number is inflated by the relatively large salaries of proceduralists like cardiologists and orthopedic surgeons who make roughly five times what peers in other developed countries earn.

Nurse practitioners make an average of $105,000 per year.

Public insurance payments to physicians differ markedly by specialty. Pediatricians make a large fraction of their income from Medicaid, since more than a third of American children are on Medicaid at any given point. Cardiologists, who treat a predominantly elderly population, make the majority of their income from Medicare.

The DRG payment mentioned above does not cover physician costs in either public or private insurance; physician services are billed separately under “Common Procedural Terminology” (CPT) codes. Most ambulatory and inpatient physician payments are still fee-for-service, with “Relative Value Units” (RVUs) converted by each insurer. The purpose of RVUs is to create a common metric to measure physician services based on the time, skill, and intensity of physician work along with practice expenses and malpractice premiums. One RVU via Medicare is worth about $36. After conversion, that $36 becomes about $56 for an office visit and about $77 for a gallbladder surgery (procedural skills are generally more valued than medical skills in the system).

The Relative Value Scale Update Committee (RUC), a 31-physician panel owned and organized by the American Medical Association, assists the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) with assigning and updating RVUs. The RUC guides ~70% of all physician payment in the United States, equal to an estimated $500 billion each year. Its recommendations are made based on survey results of only about two percent of physicians updated only every 5-20 years, but RUC recommendations are accepted without change by CMS more than 90% of the time.

Physician payments are still mostly fee-for-service with RVUs converted by the federal government, but alternative payments models developed through The Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA), like capitation, bundled payments, and global budgets, are growing in utilization, currently making up about a third of all payments.

Medicaid physician payments are mostly fee-for-service with an RVU conversion set at the state level, but managed Medicaid providers are experimenting with “capitated” payments, in which a lump sum payment is paid to the physician to encourage reduced overall spending.

The VA and IHS employ their own physicians on salary.

Pharmaceuticals consume about $500 billion, or 17%, of all health care spending.

Drug prices in the United States are 56% higher than in peer European countries and represent our single biggest source of excess health care spending. Americans make up only 4% of the world’s population, but we account for almost 80% of pharmaceutical revenue. Pharma companies point to spending on research and development, but those budgets are dwarfed by advertising budgets. Pharmaceutical and health product manufacturers account for 7.3% of all lobbying money spent in the US, while no other sector accounts for more than five percent. Pharma is by a large margin the most profitable business sector in America.

Of the 17% of the health care budget consumed by drugs, 10% is in the outpatient setting and 7% is in hospitals, nursing homes, or doctors’ offices.

Some drugs, though, are not sold through pharmacies, but through physician offices as part of the “buy-and-bill” system. The most prominent example is cancer chemotherapeutics. Medicare caps physicians at billing six percent higher than the average wholesale price. This incentivizes physicians to use more expensive drugs to generate higher payments.

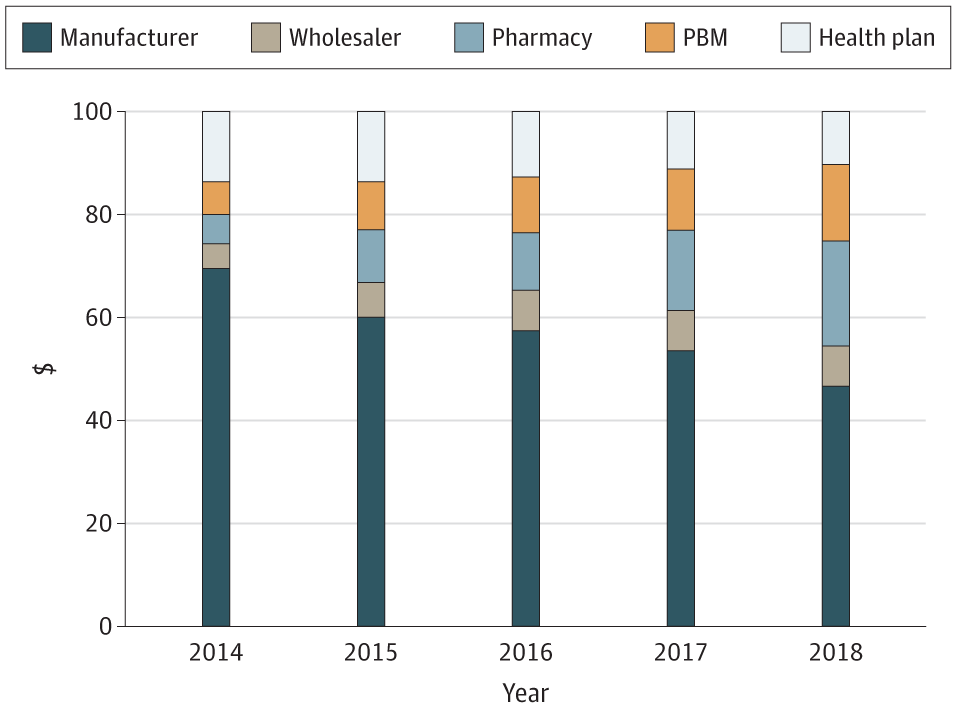

Medicare part D pays for pharmaceuticals. It is forbidden by law from directly negotiating drug prices, but is allowed do negotiate indirectly through a pharmacy benefit manager (PBM). Pharmacy benefit managers create formularies and negotiate prices in both private insurance and in Medicare. They may limit drug choices in all but six categories: immunosuppressants (as might be used in autoimmune diseases or organ transplants), antidepressants, antipsychotics, seizure medications, HIV medications, and cancer drugs.

Medicaid covers drugs on formularies determined at the state level, usually with a nominal co-payment of a few dollars per prescription.

The VA and IHS, unlike other public health insurers, are free to negotiate their own prices on pharmaceuticals. The VA by law gets at least a 24% discount from the manufacturer’s average retail price outside the federal government. Outpatient drugs are available with a copay of $5 for generics, and many vets are eligible for free prescription medications.

Dental and vision care

Medicare does not cover dental care, but some Medicare Advantage plans do.

Medicaid covers dental care for children. Coverage for adults varies by state.

Long-term care

Medicare covers part of 100 days per illness of long-term “skilled nursing care” as long as the care is triggered by a hospitalization of at least three days related to the illness needing long-term care. Coverage declines from 100% of the first 20 days down to $167/day for the remaining 80 days.

Medicaid is the primary payer for long-term care in the US, covering 62% of nursing home care and 50% of all long-term care nationally. In order for Medicaid to pay, patients must have no more than $2,000 in assets, excluding their car and a home valued up to $552,000; and require assistance with “personal care” like bathing and dressing. Medicaid requires a “look back” of five years to insure that assets have not simply been transferred to others.

What do we get from our health care spend?

Outcomes in Medicare tend to be slightly better than outcomes in private insurance. Outcomes in Medicaid tend to be slightly worse, probably owing to social determinants of health. For example, In commercial HMOs in 2018 the rate of hypertension control was 61.3% and in commercial PPOs 48.8%. Medicare rates of control were 58.9% in HMOs and 68.8% in PPOs. The Medicaid HMO rate of control was 58.9%.

After Thanksgiving we’ll talk about private insurance. Have a great holiday!

As the Medical Director of the Kansas Business Group on Health I’m sometimes asked to weigh in on hot topics that might affect employers or employees. This is a reprint of a blog post from KBGH.