Imagine, if you dare, that you are Kansas City Chiefs Head Coach Andy Reid. Fresh off two Super Bowls (and almost a third), your team now sits at 3 wins and 4 losses after a blowout defeat in which you scored zero touchdowns. You could indulge in self-pity and just listen to radio talking heads conjecture on your anticipated win-loss record come Thanksgiving.

But if your Andy Reid cosplay is true to form, I’d bet dollars-to-donuts that, instead of focusing on that intermediate outcome, you’d spend the next practice working on the process to make a better outcome more likely: fundamental skills like making sure players line up in the proper formation, know their assignments, and use sound technique in blocking, tackling, throwing, and catching. I’d bet you would want to make sure your players take care of nagging injuries.

Let’s think about the ultimate goals of medical care through this process-oriented lens. As we’ve outlined before, every medical test or treatment should aim to accomplish at least one of the following goals:

It makes the patient feel better.

If it does not make the patient feel better, the test or treatment should make the patient live longer.

Finally, if a test or treatment makes no difference in how the patient feels and makes no difference in how long the patient lives, it should at the very least save money.

If a diagnostic or therapeutic strategy can’t be proven to cause #1, 2, or 3, it isn’t worth pursuing. In this framing, weight loss is a winner: it clearly meets criterion #1. Not only does weight loss increase one’s self-esteem come bikini season (at least according to literally every magazine cover I’ve ever seen in the checkout aisle of a supermarket), it reduces the risk of multiple potentially debilitating chronic diseases, and it eases joint pain. And, as has been repeatedly shown by programs such as the Diabetes Prevention Program, which we push hard at KBGH as part of our work with CDC and KDHE, weight loss saves money (criterion #3). But in terms of #2, life prolongation, weight loss has historically fallen short. And prolonging life is maybe the thing doctors are most proud of, given our 40-year extension of life expectancy in the developed world in the last century or so.

This is a paradox.

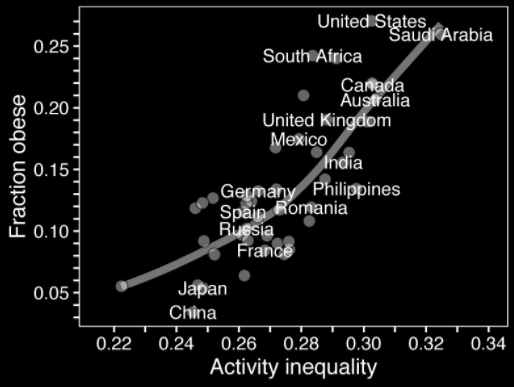

An excellent review published this week took on this paradox head-on and concluded that interventions for obesity would be more effective at preventing early death if they focused less on weight loss and more on increasing physical activity and improving fitness levels. That is, talk less about the outcome of a reduced body weight in six or twelve months, and talk more about the physical activity that will help the patient get there:

iScience

As you can see above, for any given weight, you’re less than half as likely to die of any cause if you’re cardiovascularly “fit” than if you’re not cardiovascularly fit (the word “unfit” seems a little pejorative here, but maybe that’s just me).

This isn’t necessarily new news. We’ve known for a long time that the things that happen in doctors’ offices that truly prolong life are surprisingly limited. But they’re powerful, and physical activity promotion is right there with cholesterol management, blood pressure control, and smoking cessation in terms of its potential to make people live longer. Physical activity reduces your risk of death from any cause by about 23% in a given period of time. Focusing on the process of being active daily achieves the outcome–the outcome we’re all ultimately most interested in–of a reduced risk of death, even without taking into account weight reduction.

Journal of the American Medical Association

This approach of process-over-outcomes and health at any size is provocative, but it is gaining steam. We’ll hear several speakers address the topic at the upcoming KBGH-sponsored Live Well with Diabetes Day of Discovery Event. Just as Andy Reid is surely telling his players to focus on their skills and decision making and not on their wins and losses, those speakers will likely tell us to start paying more attention to physical activity and food choices and less attention to the scale.

As the Medical Director of the Kansas Business Group on Health, I’m sometimes asked to weigh in on hot topics that might affect employers or employees. This is a reprint of a blog post from KBGH.