I had the pleasure of speaking at Envision this morning about diabetes awareness. Here are my comments:

Thank you for having me. This is not my first time speaking at Envision. It’s always a pleasure to be here. There’s an old joke that the moment a speaker steps to the lectern the crowd wonders: will this be a short, informative talk, or are we stepping into a low-key hostage situation? I promise this is not a hostage situation.

This is the story of Victoria. When we tell biographies, one of our first instincts is to say when and where someone was born. “Robert Goddard was born October 5, 1882 in Worcester, Massachusetts.” You know what I’m saying. But here’s the thing: Victoria hasn’t been born yet. Yet we already know some things about her, assuming she’ll be born in the United States. We know she’ll have a lifetime risk of developing diabetes of around 50%. A coin toss. We know she’ll have a lifetime risk of being overweight or obese of at least 70%. Way worse than a coin toss. We know that these risks will be less related to any specific decision Victoria makes than to the environment in which she is conceived, gestated, born, raised, and in which she ultimately works.

But before we get to that, you deserve to know how I make my money. I have a strange career. I’m an endocrinologist by training. That’s a doctor who specializes in metabolism and hormonal disorders. I’m still board-certified, and I still see patients at Guadalupe Clinic. But the much bigger fraction of my career is spent trying to change the way care is delivered. That sounds too simple. You know the frustration of calling for a doctor visit, waiting on hold, getting an appointment months from now, then waiting in the waiting room for a half an hour while you do paperwork, then waiting in the exam room in a paper gown for another twenty minutes, and then never even getting a copy of your labs once you’re done? That’s what I mean. That’s what we’re trying to change. More care can be delivered by non-doctors in non-offices and at the convenience of you, the patient.

One of the organizations that pays me to try to affect this change is the Centers for Disease Control, the CDC. Specifically, they along with the Kansas Department of Health and Environment pay me to try to encourage more doctors to offer care like the Diabetes Prevention Program or Diabetes Self-Management Education, or the Diabetes Self Management Program, all of which we’re going to talk about today. So be a cautious consumer. As I talk, ask yourself if you think I really believe the things I’m saying, or if I’m just a government stooge repeating words put into my mouth by my benign overlords.

I originally called this talk, “Should I go to diabetes education?” But I’ll talk about more than that.

Let’s get back to Victoria, our future, not-yet-even-a-twinkle-in-her-mom’s-eye. When Victoria grows into adulthood she’ll be told by her doctor that she needs to take in fewer calories and burn more calories in the form of physical activity or exercise. Good advice. We call these the “Big Two”: diet and exercise. And historically we’ve blamed the obesity and diabetes epidemics on decreased physical activity and increased caloric intake. The physics of it just make sense: you can’t make fat out of air. But there’s a big problem with limiting our explanation of her risk to this simple “calories in, calories out” model: the math doesn’t add up.

Intentional leisure time physical activity--that’s the kind that takes equipment, like shorts or special shoes or a bicycle or a pool--has gone up (way up) since the 1980s. Yet as a nation we’re fatter than ever. Investigators writing on the findings of a 2016 study in Obesity Research & Clinical Practice noted, “A given person, in 2006, eating the same amount of calories, taking in the same quantities of macronutrients like protein and fat, and exercising the same amount as a person of the same age did in 1988 would have a BMI that was about 2.3 points higher…about 10 percent heavier, even if they follow the exact same diet and exercise plans.”

Why is this? Why are we punished for having habits that are objectively better than those of our parents?

Well, it is no one thing. Anyone who tells you that they know the exact problem and have the precise solution is lying or excessively optimistic or both. It’s the combination of a lot of things, and like Victoria’s, our risk is teetering one way or the other long before we’re conceived, let alone born. Let’s go back to pregestational Victoria.

If Victoria’s mom is anything like most of us, we know a couple things. First, she probably carries a few extra pounds. And we know that those extra pounds carry just the slightest advantage in reproduction. That is, Victoria’s mom is ever so slightly more likely to get pregnant and carry a baby than a woman who is of a normal body weight or who is too thin. So Victoria is simply more likely to be born than someone with a very thin, non-diabetic mom would be.

The second thing we know about Victoria’s mom is that she has probably had some chronic, low-grade lead exposure, especially if she has lived her life in an urban center where dense car traffic spewed leaded exhaust into the air for decades and let it settle into the soil. The higher the lead level in Victoria’s mom’s blood, the higher Victoria’s risk for obesity, even if mom never had enough lead in her blood to be considered “lead poisoned,” and even if Victoria herself never had enough lead in her own blood to be considered dangerous by current standards.

And birds of a feather, well, you know…flock together. Victoria’s mom is likely to choose a mate whose body in some way matches hers. Or he chooses Victoria’s mom. Either way, since we know that something like two-thirds of body weight is heritable (that is, two-thirds of your risk of being thin or being heavy), having both a mom and a dad who carry extra weight puts even more pressure on Victoria’s future weight.

Since Victoria’s mom and dad have bills to pay, there’s a big chance they put off having a family. That’s the new American way. Not only the American way; the western way. The age at first birth in the United States has gone from 22 to 26 since the 1960s. And every five years parents wait to have a child, the risk of obesity in the child may go up fourteen percent.

Five years after they marry, Victoria’s mom and dad decide to get pregnant, and they have good luck. But during Victoria’s gestation, her dad encourages her mom to “eat for two.” We now know that increased fat and sugar in mom’s diet can cause “epigenetic effects” in the fetus. Remember the way DNA is put together, with A and T and C and G all writing a code that turns amino acids into proteins? Epigenetic effects aren’t changes in the A-T-C-G order of base pairs in the DNA itself; these are modifications of those base pairs, like sticking an extra branch onto the side of the “A” to keep it from coding quite as efficiently as it should. And we know one of the possible effects of these epigenetic effects may be to make Victoria more prone to weight gain and diabetes.

Finally, Victoria is born. Her mom breastfeeds her, like most moms do now, and which may have some protective effect. But after that Victoria eats what her folks buy for her: a largely government-subsidized diet that is >50% highly processed, has little fiber, and contains >2x the meat needed. We now know that this highly processed food dramatically increases our risk for weight gain and diabetes.

Investigators at the NIH recently paid twenty volunteers (ten men, ten women) to live in a research hospital for a month. They were randomly assigned to eat either an “ultra-processed” diet (think packaged meat, gravy, and potatoes) or an unprocessed diet (like fresh broccoli, cooked rice, and frozen beef) for two weeks. The diets were identical in the number of calories and amount of nutrients like fat, sugar, protein, and fiber. The volunteers were observed closely for food intake, and frequent testing was done to determine how many calories they were burning. After two weeks each person in the study was “crossed over” to the opposite diet from what they’d started on. That is, the processed diet folks started eating the unprocessed diet, and vice-versa.

What the investigators found was dramatic. In spite of having equal numbers of calories available to them at every meal and snack, the people eating the processed diet ate about 500 calories per day more than the people eating the unprocessed diet. This showed up in their weight: the processed dieters weighed, on average, 2 pounds more at the end of two weeks than they did at the start of the diet. All their extra weight was in the form of fat. And this may not have even done the effect justice: since the processed food had so little fiber, investigators had to sneak fiber into the processed food just to bring the level up to the unprocessed diet’s fiber. Without that, the results probably would have been even more dramatic.

When young Victoria turns twelve her parents decide to reward her for her good grades with new cell phone. To keep up with the social scene at school she starts sleeping with it, checking social media when she wakes up at night. As a result of this she ends up sleeping less than seven hours per night. This disrupted sleep has a measurable, clinical effect on her appetite, probably because of changes in hormone levels like ghrelin (from the stomach) and leptin (from fat).

In addition to the effect of abnormal hormones, Victoria is exposed to a lifetime of endocrine disrupting chemicals like those in air pollution, pesticides, flame retardants, and food packaging. Endocrine disruptors are chemicals that mimic or block the effects of naturally occurring hormones. Investigators in 2017 measured the amount of bisphenol A, a chemical you’ve heard of as “BPA,” in the urine of volunteers. They noted that people in the top quartile of BPA excretion, that is, the people who had more BPA in their urine than 75% of their peers, had a mean body mass index (BMI) a full point higher than people with the lowest BPA level. And BPA is one of thousands of potential chemicals we are exposed to now that were not in our environment even a few decades ago.

While Victoria eats her processed diet and takes in a strange brew of endocrine-disrupting chemicals, she lives and works in a strictly air-conditioned, heated car, office, and home that block any exposure she would normally have to hourly or seasonal temperature excursions. She’s almost never hot and almost never so cold that a cardigan can’t fix it. The effect of this may be to increase hunger. Researchers in the journal Physiology and Behavior noted that people in an office experimentally heated to 81 degrees reported decreased hunger, decreased desire to eat, feeling fuller longer. Not surprisingly, they were thirstier than their cooler peers.

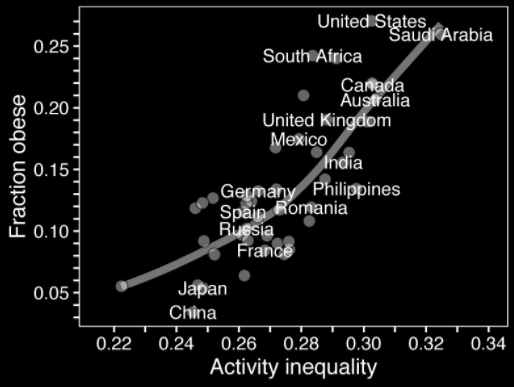

Because she lives in a cul-de-sacced suburb that is poorly designed for walkability, Victoria does not have the opportunity to walk anywhere. Not to the store, not to work. Her only opportunities for meaningful physical activity come from going to the gym. She cannot spontaneously exercise. The effect of this can be dramatic. In 2014, engineers reported in the Journal of Transportation and Health that going from an intersection density of 81 per square mile to 324 per square mile dropped was associated with a reduction in obesity from 25% to less than 5%. Similarly, going from a community design that made walking difficult to a grid-like walkable layout cut the obesity rate by a third.

Perhaps in part because of her poor sleep, processed diet, lack of exercise, Victoria becomes depressed and is put on an SSRI medication by her doctor. These medications and many others have the effect of a small but predictable amount of weight gain.

Depressed yet? Don’t be. There’s not a thing on that list that we couldn’t fix if we wanted to. But I’m not here to talk politics or policy. I’m here to talk about things you can do personally to change your risk of weight gain, diabetes, and complications of diabetes. And anyone in the room with type 1 diabetes, which is less affected by weight, don’t go away. A lot of this applies to you, too.

If you’ve heard me talk before you might be aware of Justin’s Rubric for Quality Health Care. Any potential medical test or treatment should meet one of three standards. Either:

It should make the patient feel better. This includes hundreds of treatments, like using medications and physical therapy for pain, prescribing inhalers for asthma, giving antidepressants and therapy for depression, and replacing knees. It does not, unfortunately, include much of diabetes care. Any person in the room who takes multiple doses of insulin per day and checks her blood sugar even more often than that can attest to this. Or:

If it does not make the patient feel better, the test or treatment should make the patient live longer. This applies to everyday things like checking and treating high blood pressure and high cholesterol (neither one of which make most patients feel any better or worse today) to surgery and chemotherapy for cancers (most of which make patients feel much, much worse at least in the short-term, but prolongs many lives). Or finally:

If a treatment makes no difference in how the patient feels and makes no difference in how long the patient lives, it should at the very least save money. The best example of this may be diabetes screening. As far as we can tell, screening for diabetes does not prolong life, at least not in the two or three trials that have specifically addressed the question. But diabetes screening linked to preventive measures like the Diabetes Prevention Program clearly saves money.

Diabetes was once a syndromic diagnosis, usually diagnosed when someone presented with epic amounts of urine, extreme thirst, unintentional weight loss, and sometimes strange infections. The very words we use to describe this condition give the crudeness of the diagnosis away: diabetes is from a Greek word meaning siphon, “to pass through.” Mellitus is from a Latin root word meaning honeyed or sweet. Because once upon a time, the diagnosis was confirmed by your doctor tasting your urine for sweetness.

But as our ability to test became more sophisticated, we began finding asymptomatic people with elevated blood sugars, and we had to decide who was normal and who was abnormal. It’s a tougher question than you may think, and we may still not know the answer.

So when should Victoria be screened? Or should she be screened at all? Like many questions in medicine, it depends on who you ask. Every test has risks and benefits. In the case of diabetes screening, the risks are small. There is the issue of the needlestick, but beyond that you mainly risk having an abnormal lab value on your chart. The primary benefit is financial. If Victoria is diagnosed with diabetes she can expect to spend $8,000-12,000 dollars more on medical care than the average non-diabetic person, with 12 percent of that coming out of her own pocket. Unfortunately people who are screened for diabetes and catch it early don’t seem to live longer than those who are caught according to symptoms, but they may feel better in the long run. And if we’re lucky enough to catch Victoria’s blood sugars before they rise into the frank diabetes range, we have things we can offer her.

With this in mind The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) says that anyone between the ages of 40 and 75 should be screened at least every third year. The American Diabetes Association says that screening should begin at age 45 but expands this to say that anyone as young as age 10 with certain risk factors like family history; Native American, African American, Latino, Asian American, or Pacific Islander heritage; or certain signs of insulin resistance in the skin or reproductive organs should be screened. They’ve developed a tool alongside the American Medical Assocation and the Centers for Disease Control called the Diabetes Risk Test--you can take it yourself at preventdiabeteswichita.com--that asks a few questions (some demographics, your family history, your physical activity, your height and weight) and tells you whether they think you ought to be screened.

Screening generally means a check of Victoria’s first-morning blood sugar after fasting overnight. It can’t be done with a fingerstick, so Victoria has to resist the urge to borrow a machine from her mom. It needs to be done in the lab with blood drawn from a vein.The cutoffs that we set for pre-diabetes and diabetes are, naturally, semi-arbitrary, but they’re ultimately based on the eye. If Victoria’s result is a blood sugar of 126 or above repeatedly, it means she’s diabetic. If you think 126 is kind of a strange number, you’re right. That number is set at the point where she’s more likely to develop diabetic eye disease. So it’s the eyes that make all the difference in how we define diabetes.

If her blood sugar is below 100, she’s normal. But again, if she’s over 40, most people think she should get it repeated at least every third year.

If Victoria’s blood sugar falls into that range of 100 to 125, between “normal” and “diabetic,” her best bet is to seek out the Diabetes Prevention Program, a one-year program designed to help people decrease their risk of going on to develop diabetes. The DPP, as it’s called, is sixteen weekly one hour visits with a health educator followed by eight monthly visits. In those visits you learn problem solving strategies around food choices and physical activity with the support of your coach and a team of other patients. The program has been shown to reduce the risk of going on to develop diabetes by almost sixty percent, roughly twice as effective as metformin, a common diabetes medication. In addition to simply making your numbers look better, the DPP has been shown to improve cholesterol levels, to reduce absenteeism from work, and to increase patients’ sense of well-being. For anyone insured by Medicare, the program is a covered benefit.

But what about the unlucky folks who go on to have diabetes?

We have a great program available here in town called the diabetes self-management program, or DSMP. It was developed by researchers at Stanford who were interested in making people with chronic diseases feel more in control of their lives and their destinies. It is 2.5 hours a week for six weeks, and it is taught not by a nurse or a doctor, but by a person who has diabetes herself. Investigators have determined that going through a self-management program like this reduces days in the hospital by almost two per year, probably cuts ER visits, cuts the risk of depression, and reduces low blood sugars. Best of all, it is free! If you’re interested, either ask your doctor or go to selfmanageks.org.

Last year investigators looked for randomized trials--that is, studies where patients are randomly assigned one treatment or another--of diabetes education. They included only trials that compared diabetes education with usual care, and they included only trials that lasted at least a year. Ultimately they found 42 trials that met these criteria, enrolling just over 13,000 patients and lasting an average of a year and a half. What they found was striking: diabetes self-management education significantly cut the risk of dying of any cause in type 2 diabetes patients by 26 percent. That is, a patient in the diabetes education arm of one of these studies was 26% less likely to die, by car wreck, chocolate poisoning, diabetic ketoacidosis, or any other cause, than a person receiving usual care.

In spite of this evidence, the utilization of diabetes education is disappointingly low. Only about one in five patients with diabetes ever attend.

So let’s review, very briefly. Our risk--and Victoria’s--for being overweight or obese or having diabetes begins to accrue long before we’re even conceived and is constantly modified by our environment as we age. But many of the things that affect that risk--the cleanliness of our air, the foods available for us to eat, the design of our streets, and others--are modifiable. If in spite of optimizing all those things you still find yourself with an elevated blood sugar, you have several options.

So if you think you might be at risk for diabetes, get tested. If you’re pre-diabetic, ask for a referral to the diabetes prevention program. If you’re like Victoria, if your diabetes is out of control--if your hemoglobin A1c level is higher than what your doctor would like it to be, or if you have low blood sugars--ask your doctor about getting into a diabetes education program. If your diabetes is well-controlled numbers-wise but you feel out of control, also consider going to the diabetes self-management program. The risk of the program is vanishingly low, and the potential benefit is large.