Can the Oracle of Delphi move us toward more high-value care?

Have you ever been in a meeting in which important decisions seemed to be made by or for the loudest voices in the room, even when you had a hunch that the secret consensus of the room was not in favor of the decision? If so, then you’ve been in a situation where the Delphi method would have helped.

In ancient Greece, Pythia was the high priestess of the Temple of Apollo. She was informally known as the “Oracle of Delphi.” The Oracle was consulted about important decisions throughout the ancient classical world, and her opinion was considered so valuable that Delphi was considered the center of the world. (I consider Byers, Kansas, my childhood home, the center of the world, but that fact has more to do with my robust self-esteem than it does with geographic fact or fiction.)

In modern times–the 1950s–the Delphi name was applied to a decision-making or forecasting strategy pioneered by the RAND corporation, a famous nonprofit policy think tank. (R ANd D; “research and development.” Get it?) Except this time, the decision was not to be made by an all-knowing oracle, but by the carefully considered and anonymous consensus of the group. They called it the Delphi method, and it is my favorite way to keep louder or more senior voices from always getting their way in meetings or organizations.

Here’s how it works:

A panel of “experts” is convened, usually virtually or remotely, ideally with a diverse background but some technical expertise regarding the question at hand.

Each expert is asked to make an anonymous judgement or prediction regarding the question(s).

The participants remain anonymous, even through the completion of the final report, so that those who are more senior, more vocal, or more reputable cannot dominate the decision-making. (computers have obviously made Delphi much, much easier to facilitate than it once was)

This anonymity is also meant to free participants from any embarrassment about admitting error and to prevent the “bandwagon effect,” in which faddish ideas can become popular.

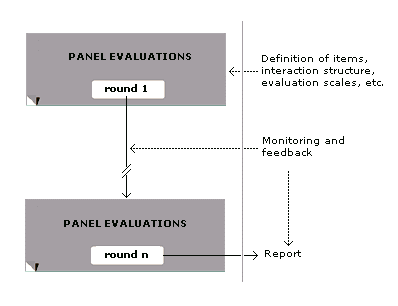

The experts’ initial answers to survey questions are collected, and irrelevant content is filtered out by a panel director. Then the survey and its answers are cycled back through the group so that others can revise their own opinions or forecasts. This process continues with a goal of gradually working toward consensus:

Wikipedia

This works for more than just complex decisions

Delphi has been adapted into “Wideband Delphi,” a technique in Scrum project management in which team members repeatedly, and anonymously, estimate the amount of time or work a project will take until they reach consensus. Then their wisdom is measured against the real-life velocity of the project to inform future estimates.

This is all prologue to what I really want to write about today, which is a solution for “guideline bloat.” Medicine, like many complex fields and like the field you likely work in, be it engineering, human resources, or accounting, continually develops and refines guidelines for use as tools to guide the screening for and care of specific illnesses. But medicine has a problem: there are too many guidelines, and they tend to encourage more care, not less. A well-known study estimated that a single primary care doc providing nothing but USPSTF screening and prevention recommendations for an everyday practice would need most of the day just for those, assuming no sick people ever came in the door. But an average primary care physician doesn’t just see people for screening and prevention, as you know. The average patient she sees has more than three problems or complaints.

So calls have come to prioritize guideline use, and some are saying that Delphi is the way to do it. In the last few weeks we’ve seen a demonstration (paywall) of how that might work. A team of investigators from several medical schools reviewed guidelines from the years 2011 through 2016 to identify “potential deintensification recommendations” in primary care medicine. That is, how can we take unnecessary care away from patients instead of adding more diagnostic work and potentially unnecessary therapies? They came up with about 50 possible recommendations and then reconfigured them to generate recommendations that 1) were actionable and measurable, and that 2) explicitly defined the deintensification action and which patients it might apply to. Then they convened a Delphi expert panel to review their synthesized evidence and judge the potential recommendations. The final work product of the panel was intoxicating if, like me, you’re the kind of person that believes that good medicine involves stopping as many treatments as you start. Here’s an example.

The original, pared-down guideline on colon cancer screening that was fed to the group of experts looked like this:

JAMA Internal Medicine

That’s a mouthful. But after a few runs through the Delphi machine, that word salad was chopped down to this:

JAMA Internal Medicine

That may still seem awkward and wordy if you’re not completely comfortable with medical jargon (FOBT is “fecal occult blood testing,” and FIT is “fecal immunochemical testing.” Enjoy your lunch). But to translate English to English, it just says that, in an average population, we should not repeat colon cancer screening very often unless past attempts at screening have been thwarted by too much poop in the patient’s colon for the doctor to be able to see through the colonoscopy camera. In other words, the health care system should not foot the bill for too-frequent cancer screening.

Two editorialists (paywall) write enthusiastically about the prospects for this kind of thinking about low-value care when low-value care is “driven by clinician behavior and a disjointed US health care system that pays for doing more, necessary or not.”

So two recommendations this week, neither of which have been run through a Delphi panel: 1) You should be using Delphi in your company if you’re not, especially if you have powerful voices that tend to dominate decision making. And 2) we should all be thinking about systematic ways like this to reduce the amount of low-value care being delivered by our healthcare system and paid for by our companies.

As the Medical Director of the Kansas Business Group on Health I’m sometimes asked to weigh in on topics that might affect employers or employees. This was a reprint of a blog post from KBGH.