As much as we’d like to think that every player in the healthcare marketplace is an integral part of the team, contributing to the health and well-being of our employees and saving employers money, it’s becoming harder and harder to support the ongoing abuses of pharmacy benefit managers, or PBMs. I won’t rehash them here. You can find past opinions about them in other posts.

Two discoveries this week at KBGH make me wonder if we’re witnessing the end of the PBM model. First, in a (unfortunately paywalled) editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine, Leemore Dafny describes the business model of a new drug company called “Civica.” Civica was launched in 2018 by seven health care delivery systems and three philanthropies to address chronic shortages of generic drugs, like IV antibiotics and sedatives, that are essential to inpatient care. Civica has since grown to sell about 50 generic injectable drugs to more than 1,500 hospital members. Their newest venture is the production of three “biosimilar” insulins (aspart, lispro, and glargine, which you may know better by their brand names Humalog, Novolog, and Lantus) that make up about 80% of the insulin market.

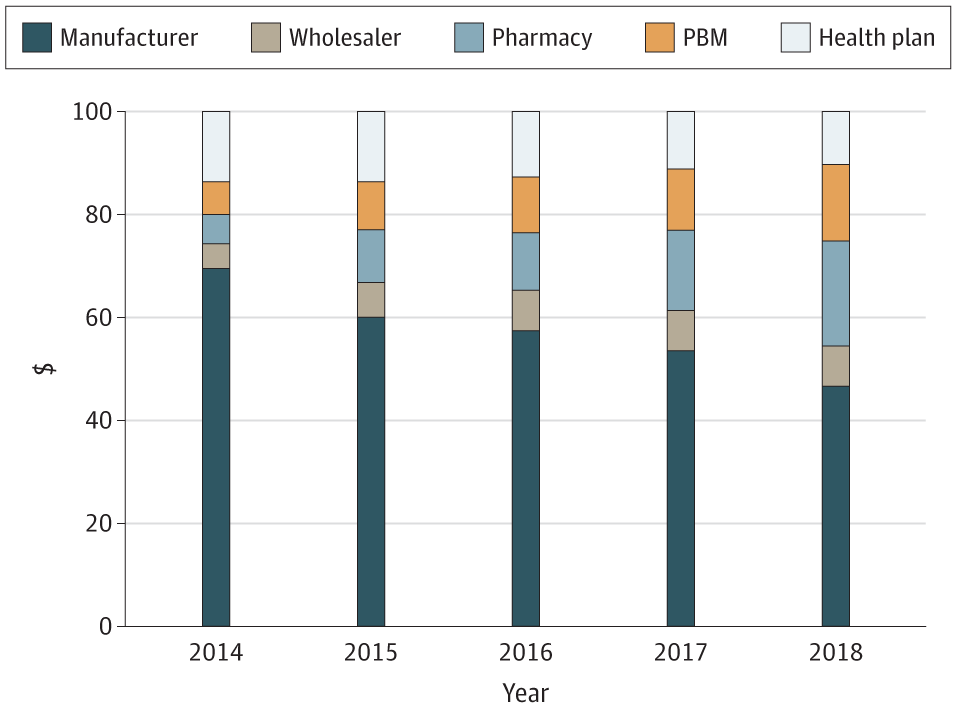

Here’s the important part: Civica intends to make its insulins available to “all U.S. pharmacies at the same wholesale price and on identical terms.” Everybody gets the same price, and Civica won’t engage in the usual PBM “rebate” trickery. It will print wholesale prices and the manufacturer’s suggested retail price right on the packaging! That MSRP will represent more than an 80% reduction from prices we’re accustomed to paying through PBMs, who keep about 60% of our money as “rebates” and other chicanery. The MSRP for a pack of five insulin glargine (a.k.a. Lantus) pens will be $55. Dafny invites us to compare that to the usual list prices of $425 for Lantus, $404 for Semglee, and $148 for unbranded Semglee.

The second cloud on the horizon for the future of traditional PBMs is Mark Cuban’s online pharmacy CostPlusDrugs.com. Instead of eliminating the PBM, Cuban has simply made the pharmacy and the PBM one and the same, with fully transparent pricing.

I don’t think we can carve the gravestone for PBMs yet; they surely have new tricks up their sleeves, and I expect legal action to be part of their strategy to try to delay companies like Civica from acting too quickly. But the tradewinds against the old, predatory PBM model seem to be blowing harder and harder. “This plan is straightforward: sell a drug at cost and at the same price to all buyers,” says Dafny of Civica. If only other health services operated the same way.

Quick tip of the hat to Drs. Bob Badgett, MD, and Kevin Wissman, PharmD, at the University of Kansas School of Medicine-Wichita for alerting us to these.

As the Medical Director of the Kansas Business Group on Health, I’m sometimes asked to weigh in on hot topics that might affect employers or employees. This is a reprint of a blog post from KBGH.